The Race Riots of May 13th 1969

"The facts of history can never be changed....

There is no need for us to hurl accusations at other races.

We should not blame a race simply because a group or individuals of that race have done wrong.........

If there is a group of Muslim terrorists, we cannot accuse all Muslims of being terrorists."

- PM Abdullah Badawi

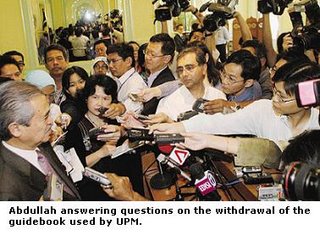

PUTRAJAYA: A controversial guidebook used by Universiti Putra Malaysia to foster closer ethnic relations among students will be withdrawn.

The decision was reached by the Cabinet after the Prime Minister spoke passionately behind closed doors on the pain and suffering he witnessed during the May 13 riots in 1969. The unanimous view was that the guidebook — which assigns blame on incidents to race groups and political parties — had no place in a course aimed at breaking down the walls of prejudice and suspicion among races.

'The facts of history can never be changed... There is no need for us to hurl accusations at other races.' - Abdullah

It will be replaced with a book drawn up by a panel of historians, the Cabinet decided during its weekly meeting. Report on New Straits Times.

Just what happened during the May 13th 1969 race riots incident? Shouldn't the government make an effort to explain to us. The younger generation. I think are matured enough to judge what is right and what is wrong. It is time the government revealed the true version to the society.

May 13 after aftermath, as seen in certain part of KL.

May 13 after aftermath, as seen in certain part of KL.According to Sejarah Malaysia :

Since independence, Malaysia was ruled by Alliance which later became Barisan Nasional in in 1971. The Barisan Nasional or National Front is a coalition of political parties. The party has easily retained its majority in Parliament throughout the nine elections held since the nation attained its independence.

However, in 1969, for the first and up till now the only time the coalition lost its overall two-thirds majority. Communal tensions resulted in the racial riots in Kuala Lumpur on 13 May 1969. The incident lead to the establishment of an emergency government, that is the National Operations Council. Tun Razak was appointed the Director of Operations under the Proclamation of Emergency for 22 months until Emergency was lifted and Parliament resumed on 22 September 1970. Since then the broad aim of the administration has been the fulfilment of the New Economic Policy which is designed to eradicate poverty regardless of race, and to eliminate the identification of occupation with race.

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, has a full page coverage about the May 13th 1969 race riots incident :

Causes Of the Riots.

The May 13 Incident is a term for the Chinese-Malay race riots in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on May 13, 1969. The riots continued for a substantial period of time, and the government declared a state of national emergency, suspending Parliament until 1971. Officially, 196 people were killed as a result of the riots between May 13 and July 31, although journalists and other observers have given much higher figures.

The government cited the riot as the main cause of its more aggressive affirmative action policies, such as the New Economic Policy (NEP), after 1969. The riot has also since been used in election campaigns and political rallies, typically to browbeat Chinese opposition into accepting government policies.

On its formation in 1963, Malaysia suffered from a sharp division of wealth between the Chinese, who were perceived to control a large portion of the Malaysian economy, and the Malays, who were perceived to be more poor and rural. However, it was foreign individuals and organisations, not the Chinese, who held the largest portion of total corporate equity in the country.

1964 Race Riots in Singapore were a large contributing factor in the expulsion of that state from Malaysia, and racial tension continued to simmer, many Malays dissatisfied by their newly independent government's perceived willingness to placate the Chinese at their expense.

Politics in Malaysia at this time was mainly Malay-based, with an emphasis on special privileges for the Malays — other indigenous Malaysians, grouped together collectively with the Malays under the title of "bumiputra" would not be granted a similar standing until after the riots. There had been a recent outburst of Malay passion for ketuanan Melayu — Malay supremacy — after the National Language Act of 1967, which in the opinion of some Malays, had not gone far enough in the act of enshrining Malay as the national language. Heated arguments about the nature of Malay privileges, with the mostly Chinese opposition mounting a "Malaysian Malaysia" campaign had contributed to the separation of Singapore, and inflamed passions on both sides.

The causes of the rioting can be analysed to have the same root as the 1964 Race Riots in Singapore. In addition, Malay leaders who were angry about the election results used the press to attack their opponents, contributing to raising public anger and tension among the Malay and Chinese communities.

Singaporean prelude

In the afternoon of 21 July 1964, over 20,000 Malays and Muslims had assembled at the Padang to celebrate the birthday of Prophet Muhammad. The celebration was an annual affair. Something different happened that year. Leaflets calling on Malays to destroy the PAP government were distributed earlier. Even the Yang Di Pertuan Negara, Yusof Ishak, was jeered at by some organisations during his speech.

As part of the celebrations, contingents from the various organisations and societies were to march from the Padang to Lorong 12, Geylang. Along the way, near Kallang, a clash between a Chinese policeman and a group of Malays sparked off the 1964 race riots.

Singapore was put under a curfew that allowed people to leave their houses only at certain times of the day. When the curfew was lifted on 2 August 1964, 23 people had lost their lives while another 454 people had been injured.

It is speculated that the riots were not spontaneous expressions of bad feelings between the races but rather were deliberately started by rumours, exaggerations and lies that were created to arouse racial and religious hatred among the Malays. By putting the blame for the riots on the Singapore government, it was hoped that the Singapore Malays would gather around Malaysia's government UMNO for protection.

May 1969 riots

In the May 10, 1969 general elections, the ruling Alliance coalition headed by the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) suffered a large setback in the polls. The largely Chinese opposition Democratic Action Party and Gerakan gained in the elections, and secured a police permit for a victory parade through a fixed route in Kuala Lumpur. However, the rowdy procession deviated from its route and headed through the Malay district of Kampung Baru, jeering at the inhabitants. Some participants brandished banners and placards bearing slogans such as "Kuala Lumpur sekarang China punya" (Kuala Lumpur now belongs to the Chinese), "Orang Melayu balik kampong" (Malays go back to the villages), "Melayu sekarang tidak ada kuasa lagi" (Malays now no longer have power), and "Semua Melayu kasi habis" (Finish off all the Malays). Some demonstrators carried brooms, later alleged to symbolise the sweeping out of the Malays from Kuala Lumpur, while others chanted slogans about the "sinking" of the Alliance boat — the coalition's logo.

While the Gerakan party issued an apology the next day, UMNO announced a counter-procession, which would start from the Selangor Chief Minister Harun bin Idris' home in Jalan Raja Muda. Tunku Abdul Rahman would later call the retaliatory parade "inevitable, as otherwise the party members would be demoralised after the show of strength by the Opposition and the insults that had been thrown at them."

Shortly before the procession began, the gathering crowd was reportedly informed that Malays on their way to the procession had been attacked by Chinese in Setapak, several miles to the north. The angry protestors swiftly wreaked revenge by killing two passing Chinese motorcyclists, and the riot began. During the course of the riots, the loudspeakers of mosques were used to urge the rioters to continue in their actions.

The riot ignited the capital Kuala Lumpur and the surrounding state of Selangor, but except for minor disturbances in Melaka the rest of the country stayed calm. A nationwide state of emergency and accompanying curfew were declared on May 16, but the curfew was relaxed in most parts of the country for two hours on May 18 and not enforced even in central Kuala Lumpur within a week.

According to police figures, 196 people died , 149 were wounded and many women were raped. 753 cases of arson were logged and 211 vehicles were destroyed or severely damaged. An estimated 6,000 Kuala Lumpur residents — 90% of them Chinese — were made homeless. Various other casualty figures have been given, with one thesis from a UC Berkeley academic putting the total dead at ten times the government figure.

Conspiracy theories

Immediately following the riot, conspiracy theories about the origin of the riots began swirling. Many Chinese blamed the government, claiming it had intentionally planned the attacks beforehand. To bolster their claims, they cited the fact that the potentially dangerous UMNO rally was allowed to go on, even though the city was on edge after two days of opposition rallies. Although UMNO leaders said none of the armed men bused in to the rally belonged to UMNO, the Chinese countered this by arguing that the violence had not spread from Harun Idris' home, but had risen simultaneously in several different areas. The armed Malays were later taken away in army lorries, but according to witnesses, appeared to be "happily jumping into the lorries as the names of various villages were called out by army personnel".

Despite the imposition of a curfew, the Malay soldiers who were allowed to remain on the streets reportedly burned several more Chinese homes. The government denied it was associated with these soldiers and said their actions were not condoned.

Repercussions of the riot

Immediately after the riot, the government assumed emergency powers and suspended Parliament, which would only reconvene again in 1971. It also suspended the press and established a National Operations Council. The NOC's report on the riots stated, "The Malays who already felt excluded in the country's economic life, now began to feel a threat to their place in the public services," and implied this was a cause of the violence.

The riot led to the expulsion of Malay nationalist Mahathir Mohamad from UMNO and propelled him to write his seminal work The Malay Dilemma, in which he posited a solution to Malaysia's racial tensions based on aiding the Malays economically through an affirmative action programme.

Tunku Abdul Rahman resigned as Prime Minister in the ensuing UMNO power struggle, the new perceived 'Malay-ultra' dominated government swiftly moving to placate Malays with the Malaysian New Economic Policy (NEP), enshrining affirmative action policies for the bumiputra (Malays and other indigenous Malaysians). Many of Malaysia's draconian press laws, originally targeting racial incitement, also date from this period.

The National Security Commission published an official report about the incident on October 9, 1969, pointing the finger at the Malayan Communist Party and illegal Chinese gangs for causing the riots.

The Rukunegara, the de facto Malaysian pledge of allegiance, is another reaction to the riot. The pledge was introduced on August 31, 1970 as a way to foster unity among Malaysians.

Another article of same topic can be viewed at Noworks Encyclopedia.

"May 13 - Before and After"

( Excerpts of this book by (the late) Tunku Abdul Rahman, then Prime Minister of malaysia, published in September 1969 )

"Victory" on the rampage

No one was more surprised, I am sure, than the DAP and the newly-formed Gerakan with their unexpected successes. They felt not only cocky, but downright arrogant. They lost no time in arranging to celebrate their "victories."

Dr. Tan Chee Khoon, who won his seat in Batu Selangor, with a big majority asked for Police permission to hold a procession by members of his Gerakan Party. A permit was granted on condition that it followed a route authorised by the Police.

(On 12th May) Dr. Tan's victory procession was held on an unprecedented scale, politically speaking, and was accompanied by acts of rowdyism and hooliganism and in utter defiance of the Police after the main procession had ended.

The procession went through unauthorised routes, jamming traffic everywhere as a consequence. With victory emotions on the loose and - there can be no other explanation - Communists urging them on, the victors made a serious blunder, and blunder it was.

The procession shouting its way along turned into Jalan Campbell and Jalan Hale - roads on the edge of an leading into Kampong Bahru where 30,000 Malays have lived in peace for years beneath the palms in their own settlement in the centre of Kuala Lumpur.

Jalan Hale is the main street of Kampong Bahru. There they proceeded to provoke the Malays, gibing at them and throwing their victory in their faces in the midst of what is virtually an UMNO stronghold.

On Tuesday, May 13th Gerakan Party's Yeoh Tech Chye, the President of the Malaysian Trades Union Congress (who won big in Bukit Bintang, Kuala Lumpur) made an open apology in the press for his party supporters having caused such inconvenience to the public.

But the emotional damage had already been done.

I returned to Kuala Lumpur about lunchtime from Alor Star. My Principal Private Secretary informed me that he had received news that a counter demonstration was to be held on May 13th as the Malays were very annoyed.

UMNO was going to stage a procession to celebrate it's victory and that a crowd would gather in the compound of the house of the Menteri Besar of Selangor, Dato Harun bin Idris, in Jalan Raja Muda and that the procession would start from there.

I was personally worried that the procession might lead to trouble. It was not easy to stop it at this stage as the Opposition had already held processions, and permission had already been obtained for UMNO to have theirs.

May 13th

..…A phone call came through at 6.45pm that an ugly incident had taken place along Jalan Raja Muda in which some Chinese were assaulted.

Immediately afterwards Enche Mansor, the Kuala Lumpur Police Traffic Chief, and one or two others, came to see me and said that there had been killing. The city had been placed under immediate curfew as at 7 pm. The Security Forces were out, the army called in.

Naturally I could not sleep that night, my mind upset with the tragedy that had overtaken our peaceful capital and nation. I went out side my balcony outside my room looking down on the city in the valley by night. Flames were burning high in several areas, near Kampong Bharu and to the North.

Kuala Lumpur was a city on fire and it was a sight that I never thought I would see in my lifetime.

While they were gathered in the compound of Dato Harun's residence news came through suddenly that Chinese had attacked Malays in Setapak, a mile or two to the North, as they were on their way to join the procession starting from Jalan Raja Nuda.

The news created a storm of indignation; hell broke loose. Two Chinese passing by on motor cycles were attacked and killed. And so the riots of May 13th began, triggering off violence unprecedented in the history of Malaysa.

(A state of emergency was declared on May 16th and a National Operations Council set up to deal with all matters pertaining to it. The first act: round-the-clock curfew.)

..Within 48 hours it was possible for the Council to approve relaxation in the curfew in many areas of the country.

Even in the most sensitive ares, Kampong Bharu and the Jalan Chow Kit sections of Kuala Lumpur, where the violence had originated, it was possible after one week from the outbreak to announce curfew relaxations there.

There was no insecurity in the East Coast states. In Johore and Negri Sembilan no incidents had occurred at any time. In Malacca there had been a few minor troubles and they had now ceased as quickly as they had started.

There were no incidents taking place in Perak and Penang, Kedah and Perlis.

Apart from Kuala Lumpur, the only sections in the country needing the strictest vigilance were in the Betong salient, the rural areas along the Kedah and Perak borders with Thailand.

The general situation, however, was far from normal, mainly for one particular reason - rumours.

During the height of the disturbances rumour-mongering was wild and widespread as always happen anywhere in time of riot.

View above article at little Speck.

2 Comments:

I just feel that the UMNO counter-procession should have been delayed;at least till soaring temperatures had settled.

Just feel that the UMNO counter-procession should have been deferred;at least till soaring temperatures had settled.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home